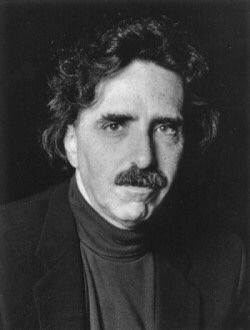

Artist/Educator Archive Interview - Dr. Theodore Edel |

|||

e regularly feature the personal experiences and insights of a noteworthy artist/educator on various aspects of piano performance and education. You may not always agree with the opinions expressed, but we think you will find them interesting and informative. The opinions offered here are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily represent those of the West Mesa Music Teachers Association, its officers, or members. (We have attorneys, too!). At the end of the interview, you'll find hypertext links to the interviewee's e-mail and Web sites (where available), so you can learn more if you're interested. Except where otherwise noted, the interviewer is Dr. John Zeigler.

|

|||

|

The May 1999 artist/educator:

I can’t remember a time in childhood when I did not hear music; it was always there. And growing up in New York City meant continual exposure to such a great number of pianists.

I was fortunate in having four wonderful teachers. Edgar Roberts in the Juilliard Preparatory Division was the first to make me aware of the possibility of refining each phrase, every pedal change. His standards were demanding. My teacher in the upper division at Juilliard, Jacob Lateiner, had a depth of musical understanding that was very special. Arminda Canteros, a distinguished teacher of the physical act of piano-playing, taught me to relax, gave me freedom of movement and freedom from tension. I still think of her sometimes when I put my hands on the piano, and of course when I teach young people to use their hands. Later on, Constance Keene dealt with the important essentials of projection, performance, and musical characterization.

Making music is the ultimate challenge, because it engages all our faculties: the hand, heart, and mind must all contribute fully. It’s like the old Jewish joke: There’s a job being offered, which is to stand at the edge of the village waiting for the Messiah to arrive. It doesn’t pay well, but it’s a lifetime job. When we work at great music we have a chance for an intimate relation with greatness. The composers we revere are really in our lives, which is a moving experience. Teaching involves sharing a lifetime of knowledge with a young person. There are times when I’m aware that decades of study and experience are going into this particular moment.

I use Dohnanyi, Philipp, Hanon, sometimes the Brahms 51 Exercises. And, of course, the bread and butter of technique — scales and arpeggios (and scales in thirds). I do not like exercises with long-held notes; it is the rare student who can avoid tension when part of the hand is pinned down. More important than which method we use is that, in the technical work, we strive for perfection. That is, absolute evenness, together with natural, relaxed movements and the absence of all strain. The drill should be "perfect".

The most common physical problem is stiffness in the wrist — playing melodic notes without suppleness, loud chords without "rebound" and elasticity, and spread-out patterns done without freeing movements of the arm and wrist. Another problem is a lack of patience in practicing — they go too fast to achieve evenness and accuracy. Many youngsters pay little attention to the score. Not only are they uninformed about the signs and the meaning of the composers’ instructions to us, but they don’t even realize the importance of being true to the score. Some have not heard enough music, which directly relates to another problem. People play for years without asking themselves a crucial question: what is the character of the music? Another element that comes to mind is the pedal in all its refinement. It would be hard to overstate the importance of good pedaling in making or breaking a performance.

Well, to continue with what I was just saying about practicing, I have some general rules. First of all, practicing means "doing it right". The tempo in which you can do it perfectly (and not needlessly slow either) is the only desirable tempo. This requires some self-knowledge and also the greatest gift of all: patience. We should build up the piece with great care, as if building a house to live in. Our practicing should have a goal. Don’t give yourself credit for just playing through this movement for the umpteenth time. Practice means to change your performance. Always work on the parts that you can’t do. Play what you know just once, but the challenging sections dozens and dozens of times. In the end, this is the most rewarding kind of work. For teachers I would offer three suggestions. Don’t let a student focus only on contests. Think about musical literacy, the complexity of Bach’s Preludes and Fugues, études that may take a year to master, a broad range of composers, etc. Consider hand size: don’t push the young ones into octaves and big Romantic repertoire too early. And try to choose un-hackneyed, lesser-known pieces. In my experience, judges and critics listen to them more kindly and with fewer preconceptions.

Contrary to a false (though popular) adage, we musicians know that "Those who can, teach." So the more we develop our playing, and also our understanding of the many components of good playing, the further along we are. The most valuable teaching is by example. Try to see and understand music in the broadest terms. Relate the piano repertoire to the whole of music — singing, string quartets, symphonies — especially with composers like Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert, whose keyboard output was only a part of their vast artistic "world." The teacher who has the Mozart operas in his/her blood — and tries to make his piano sonatas breathe and come to life with real character — is not the same as the teacher who approaches them simply as piano music. At the same time, there is certainly a lot to learn from listening to fine piano recitals and from recordings.

A career in music has always been very difficult, but it has become considerably more so. Every year there seem to be greater numbers of superb pianists, but "the job is already taken". And then there is the painful fact that merit is just one of the criteria for success. Music as a career is only for people who absolutely need it deep from within.

Competitions are in a sense unfortunate — disappoint the many to encourage the few. But for younger students they do represent a tangible goal to work for, especially today when there are so many other activities and distractions. I know I’m not alone in being able to name children who would never go to the piano without a contest looming. For both youngsters and pre-professionals, it’s a chance to perform under pressure. The Russian philosopher Gurdjiev used to say: "Every day do something you’re afraid of." I try to encourage an accepting attitude among my students, always stressing the fact that judging is highly subjective. We have all seen inexplicable results in contests, so we need to prepare our students for possible defeat. It doesn’t mean they’re failures in any sense of the word. There is such a danger of exaggerated reactions. I’ve seen students quit the piano in discouragement, or at least distance themselves from music. More amazing, I’ve seen cases where children, as a result of winning, retire from music. They’ve finally won the big prize that they (their mothers, really) have been seeking, and there is nothing more to accomplish!

Teaching: seeing my 14-year-old student win first prize in the Chicago Symphony’s Young Performer’s Concerto Competition, live on television. Performing: playing an all-Liszt recital at the Institute of the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest. The School was founded by Liszt himself, he lived nearby for years, and his spirit seems to hover everywhere.

This problem of the growing marginalization of classical music is bigger than any one teacher can surmount. But concert-going is a help. Many parents don’t take their children to live music, so there are students who only hear their peers and the occasional CD. This is not inspiring. I remember the excitement of being taken to Brooklyn as an eight-year-old to hear Emil Gilels tear through the "Appassionata" Sonata — this stayed with me for years, even his wrong notes!

I will never forget the many concerts Sviatoslav Richter gave in New York. The intensity of his approach, the commitment to every note, and of course the phenomenal execution — the miracles that came out of the piano! Whether or not some interpretations seemed contrary to the composer’s attention, the concert seemed for him a matter of life and death, and so it became so for us as well. He was, in the truest sense, a presence. Claudio Arrau, particularly in Schumann and Liszt, had a depth of feeling, a kind of profound generosity of soul that was especially moving. He probed the music with a high degree of seriousness that served as a reminder of the very purpose of music as an art. Of course, Richter and Arrau were very famous, but I think that we have to shed the preconception that fame and greatness always go together. Careers are so dependent on chance. For example, for me the recordings of Vladimir Sofronitzky are extraordinary: I can’t imagine Romantic music being played better. But how many people outside of Russia have heard of him? Actually, every fine artist has his/her great moments. I think of Horowitz on television, playing the slow Etude in C# minor by Scriabin; it brought tears to my eyes. Haydn’s Sonata No. 49 in E-flat played by Brendel in Carnegie Hall was scintillating and thoroughly right from first note to last. But I can’t imagine them reversing the repertoire with similar effect. And haven’t we all heard wonderful performances from artists who are quite unknown? So I think we need to be open-minded and seek out excellence wherever we can find it.

Set high standards in both the pieces and the technical drill, but be generous with praise. Make students feel good about themselves. As a student, I used to accompany the violin lessons of Dorothy DeLay. One of her secrets was that she made the students so comfortable, always finding something to praise in their performances. Have frequent workshops: playing for others builds confidence. Never create rivalry by playing one student against another. Remind yourself that each student has different strengths and moves at a different speed. Sometimes we just need to wait patiently, like a good gardener.

The greatest joy is sharing a lifetime of experience and study of music with bright young people, watching them develop into good players and sound musicians. The greatest frustration is that you only see them for one hour in a long week. Where is the time to guide their practicing, or listen to operas and symphonies together? At so many lessons I say "At home, you’re the teacher, you’re the coach." But are they? I wonder.

One day my wife wondered aloud whether anyone had made a thorough study of the one hand literature, and that it would meet a valuable need for pianists and teachers. A light bulb went off when I realized that, indeed, no one had ever done so.

Of course, we are really talking about two literatures — one for the left and the other for the right. There are four main reasons for the left hand repertoire. It all began as a stunt in the carnival-like atmosphere of the early piano recital (the 1840s and 50s). Alexander Dreyschock and Adolfo Fumagalli, two of the most important purveyors, were simply showing off. Then in the latter part of the 19th century, as the level of playing rose and piano pedagogy was codified, dozens of etudes appeared whose purpose was to shore up the disparity in skill between the two hands. Injury has played a major role, particularly in the 20th century with the many commissions from Viennese pianist Paul Wittgenstein. Some composers have responded to the challenge of limitations: how much can be accomplished with five fingers? Brahms said that he played with his left hand alone in order to "feel like a violinist"; from this arose his arrangement of the Bach Chaconne. The fugues by Reger, Dohnanyi, and Godowsky represent "mind over matter". With his left hand Paraphrases on Chopin Etudes, the master pianist Godowsky was out to revolutionize piano writing itself. Written a century ago, these 22 pieces represents the pinnacle of the left hand literature and have never been equaled in terms of difficulty and ingenuity. All of these motivations for left hand music help to explain the paucity of right hand works. Dreyschock and Fumagalli could never have advanced their careers an inch with music for the right hand alone. In fact, most of the two-hand music by those early virtuosi was in a sense "for the right hand" — glittery, light-weight concoctions designed to show off digital skills in the brilliant new upper reaches of the keyboard. As for technical development and challenge the standard repertoire has always been a gold mine for the right hand. And finally injury: it seems that few pianists have damaged their left hands either away from the piano or while practicing.

I can assure all the left hand players that they will find enough material to last them longer than one lifetime. In my book, Piano Music for One Hand (Indiana University Press), I discuss over 1000 left hand works by 350 composers. The range of difficulty here absolutely parallels the standard piano literature, from children’s materials to the dizzy heights of Godowsky — and every stage in between. What’s missing is the "immortals" like Chopin, Schumann, Brahms (except as an arranger of Bach), Liszt (except a simple late work), etc. The big names in the left hand solo literature are Scriabin, Saint-Sans, Moszkowski, and Reger. And since the genre began in the mid-19th century and had its heyday during the following decades, the Baroque and Classical styles are found only in transcription. From the psychological viewpoint it seems to take considerably more nerve to perform with the left hand alone, harder to feel that edge of confidence. And the memory requires more repetitions, at least it does for me and others with whom I’ve spoken. But some pianists may not find this to be true. As for the right hand, I mention 60 composers in my book, but see my article in Piano & Keyboard (May/June, 1998) for several others (plus some musical examples). In contrast to the left hand repertoire, all but two works are from the modern period. Some of the names here are Vivian Fine, Jean Absil, Richard Rodney Bennett, Allen Shawn, Louis Calabro, and Ned Rorem. Strangely enough — and this will disappoint anyone seeking display repertoire — the right hand works are devoid of virtuosity. Not only are they far easier than the left hand solos, but even simpler than the parts we think of as challenging in our standard two-hand repertoire. Pianists looking for right hand music — those with left hand injuries and teachers dealing with such students — should also try adapting left hand pieces. With simple music there’s no problem, but the more idiomatic and difficult the writing is, the more impractical this becomes. To give one example: Scriabin’s Prelude in C# minor is technically quite easy and can be played nicely by the right hand, but his more difficult and widely-ranging Nocturne would be awkward. I encourage all pianists to explore the entire literature fully, meet the challenges, and make whatever changes are necessary. The main point is to be active and to make music.

Yes, left hand playing can be strenuous. A half hour of even moderately fast music can bring on fatigue: all the fingers used constantly and sometimes in unfamiliar positions; the effort of bringing out certain notes. It's important to consciously lighten up the dynamics, keep calm while practicing the exciting parts, and make sure the wrist is relaxed at all times. Sitting one octave to the right of middle C is helpful: the wrist doesn't have to turn so much. When the left hand has to go high into the treble, shift the torso far over, holding on to the corner of the piano with your right hand. Even in middle-range passages, holding on to the bench with the right hand serves as an anchor. With all of that said, there is one thing that makes the left hand superior for piano playing: the strong fingers are on the right side, well-suited for bringing out the melody. Of course, composers sometimes put the melody on the bottom too!

Few people realize that Wittgenstein received seventeen concerti (some were never published). But you are right: the Ravel is the best, simply because it’s genuinely great music. If he had written it for two hands it would definitely be in our repertoire. (Actually Ravel, who was not the world’s greatest pianist, did have to use both hands when he played it for Wittgenstein the first time). Another good concerto is the Diversions by Britten. I find the two Strauss works, as well as Prokofieff’s No. 4, uninspired. The score by Hindemith, which Wittgenstein rejected, has completely disappeared. Among Wittgenstein’s best commissions are three Quintets by Franz Schmidt. A less-known pianist who lost his right arm in the first World War was the Czech Otakar Hollmann, who convinced Martinu and Janácek to write for him (a concertino and a chamber work respectively). Turning to the solo repertoire, the Godowsky Paraphrases on Chopin Etudes are miracles of piano writing. While most are beyond the average pianist, the E-flat minor, Op. 10 No. 6, is approachable; Raymond Lewenthal wisely chose it for his excellent anthology Music for One Hand (Schirmer). At the top of the list comes Scriabin’s Prelude and Nocturne, op. 9, which, like Ravel’s Concerto, would be played even if he had scored them for two hands. Other Romantic repertoire I recommend are the études (character pieces, really) by Blumenthal, Sauer, and Reger. Saint-Saëns’ 6 Etudes are much simpler. Moszkowski was not a deep composer, of course, but his 12 Etudes cover the whole spectrum of technique. Though little-known today, Alexis Hollander and Josef Rheinberger were distinctly superior salon composers. Bartok’s 1903 Etude, is exciting but a bit long, and a surprising example of his early style; it requires excellent octaves. For sheer musical worth, nothing can top Bach’s violin Chaconne as arranged by Brahms; it’s fairly difficult. For teaching young children, the volume Piano Music for One Hand by Australian Composers (Allans) is filled with charming things. In the modern idiom there are important works from Willem Andriessen, Joseph Dichler, Robert Helps, Marcel Mihalovici, Franz Schmidt, and Jeno Takacs. Robert Saxton’s complex Chacony is one of several works recorded by Leon Fleisher. The avant garde Etude pour agresseurs by Alain Louvier is scored for fingers, palms, wrists, and forearms.

The concerti and chamber works are well represented on disk. Leon Fleisher has a solo CD with excellent renditions of Saint-Saëns, Blumenfeld, Scriabin, Godowsky, Takacs, and Saxton. Geoffrey Madge recorded all the Chopin-Godowsky Paraphrases; Ian Hobson plays a selection. I did a Web search which turned up isolated recordings of single pieces by Nepomuceno, Ponce, Lipatti, Mompou, and Moszkowski; Josef Hofmann recorded his own Etude. That's a tiny percentage of the left hand solo repertoire. As far as the right hand is concerned, Lionel Nowak made a cassette of some significant works written for him (available from the Bennington College Office of Public Affairs).Anyone who wants to explore the left hand literature with real thoroughness will have to look at the music, either through inter-library loan or a visit to a major national library. The nice thing about one-hand music is the comparative ease of sight-reading.

Definitely, yes. Left hand music is good for everyone. Is there a pianist whose left hand is equal to his/her right? I doubt it, because during the years spent working at the standard repertoire our right hands are continually in the spotlight. With music for the left hand alone, we can focus on any imperfections which may be partly hidden by the busy right hand. We can refine and set higher standards not only in technical matters, but the balance, phrasing, and dynamic gradations. Many students now playing Chopin’s "Revolutionary" Etude might gain more from careful work on a couple of Moszkowski Studies. I consider Godowsky’s Paraphrase of the Chopin Etude in A minor, op. 10 no. 2 (for the fourth and fifth fingers) to be the greatest of all technical drills, if practiced with a free wrist and not too loudly. As for recital repertoire, left hand music offers a distinct novelty for the audience — but it probably won’t make you rich and famous like Dreyschock!

There are now excellent teachers everywhere, so as far as the level of playing and training are concerned, I would guess the future is bright. With great puzzlement I have read and heard about the supposed decline in piano-playing (and singing too). I heartily disagree, and I applaud the pianists of today! I would say that an unprejudiced study of old and new recordings shows that, except for an extremity of rubato in certain Romantic works, some "great" pianists of the past do not necessarily meet our ideals of what a good pianist should be, in terms of technical precision, stylistic distinctions, attention to instructions in the score, range of repertoire, and yes, even sensitivity — the kind that harmonizes with the composer's intentions. We love the things that helped form us when we were young and impressionable. But although Richter and Arrau meant a lot to me at a particular time, I hope I will never say that they represent some kind of "lost world". While the number of fine players keeps growing, the audience for classical music in general does not (perhaps with the exception of opera). Fewer families feel compelled to enrich their children's lives with traditional classical piano lessons than did in the past, which may in the future jeopardize a portion of the audience for piano recitals. So, while I am confident that the piano will be played and taught at a wonderfully high level, I can't help feeling concerned for the pianist's future place in society. You can ask your own questions of Dr. Edel by e-mail to: tedel@uic.edu |

||

|

Page

created: 5/25/99 Last updated: 02/09/24 |

Dr. Theodore Edel, Associate Professor,

Dr. Theodore Edel, Associate Professor,